Pregnant ladies wielding swords and carrying martial helmets, fetuses set to avenge their fathers—and a harsh world the place not all newborns have been born free or given burial.

These are among the realities uncovered by the primary interdisciplinary research to concentrate on pregnancy in the Viking age, authored on my own, Kate Olley, Brad Marshall and Emma Tollefsen as a part of the Body-Politics project. Regardless of its central function in human historical past, being pregnant has typically been neglected in archaeology, largely as a result of it leaves little materials hint.

Being pregnant has maybe been notably neglected in durations we largely affiliate with warriors, kings and battles—reminiscent of the highly romanticised Viking age (the interval from AD800 till AD1050).

Matters reminiscent of being pregnant and childbirth have conventionally been seen as “ladies’s points”, belonging to the “pure” or “non-public” spheres—but we argue that questions reminiscent of “when does life start?” are by no means pure or non-public, however of serious political concern, right now as previously.

In our new research, my co-authors and I puzzle collectively eclectic strands of proof to be able to perceive how being pregnant and the pregnant physique have been conceptualized at the moment. By exploring such “womb politics”, it’s potential so as to add considerably to our information on gender, our bodies and sexual politics within the Viking age and past.

First, we examined phrases and tales depicting being pregnant in Outdated Norse sources. Regardless of courting to the centuries after the Viking age, sagas and authorized texts present phrases and tales about childbearing that the Vikings’ rapid descendants used and circulated.

We discovered that being pregnant could possibly be described as “bellyful”, “unlight” and “not complete”. And we gleaned an perception into the potential perception in personhood of a fetus: “A girl strolling not alone.”

Wiki Commons

An episode in one of many sagas we checked out helps the concept that unborn youngsters (no less than high-status ones) may already be inscribed into complicated techniques of kinship, allies, feuds and obligations. It tells the story of a tense confrontation between the pregnant Guðrún Ósvífrsdóttir, a protagonist within the Saga of the People of Laxardal and her husband’s killer, Helgi Harðbeinsson.

As a provocation, Helgi wipes his bloody spear on Guđrun’s garments and over her stomach. He declares: “I believe that below the nook of that scarf dwells my very own dying.” Helgi’s prediction comes true, and the fetus grows as much as avenge his father.

One other episode, from the Saga of Erik the Red, focuses extra on the company of the mom. The closely pregnant Freydís Eiríksdóttir is caught up in an assault by the skrælings, the Norse title for the indigenous populations of Greenland and Canada. When she can not escape resulting from her being pregnant, Freydís picks up a sword, bares her breast and strikes the sword towards it, scaring the assailants away.

Whereas generally considered an obscure literary episode in scholarship, this story could discover a parallel within the second set of proof we examined for the research: a figurine of a pregnant lady.

This pendant, present in a tenth-century lady’s burial in Aska, Sweden, is the one recognized convincing depiction of being pregnant from the Viking age. It depicts a determine in feminine costume with the arms embracing an accentuated stomach—maybe signaling reference to the approaching youngster. What makes this figurine particularly attention-grabbing is that the pregnant lady is carrying a martial helmet.

Historiska Museet, CC BY-ND

Taken collectively, these strands of proof present that pregnant ladies may, no less than in artwork and tales, be engaged with violence and weapons. These weren’t passive our bodies. Along with recent studies of Viking women buried as warriors, this provokes additional thought to how we envisage gender roles within the oft-perceived hyper-masculine Viking societies.

Lacking youngsters and being pregnant as a defect

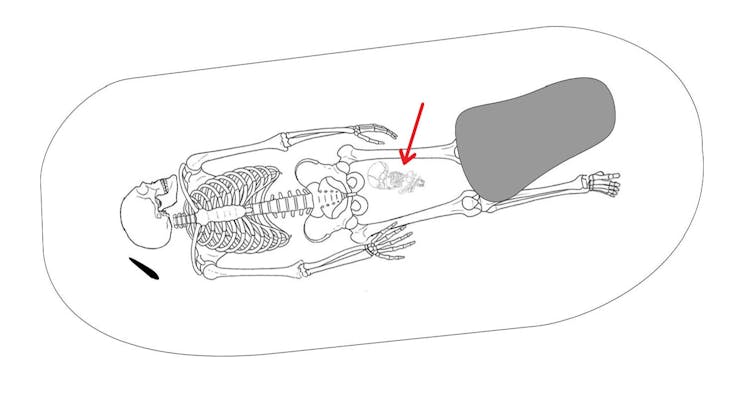

A ultimate strand of investigation was to search for proof for obstetric deaths within the Viking burial file. Maternal-infant dying charges are regarded as very excessive in most pre-industrial societies. But, we discovered that amongst 1000’s of Viking graves, solely 14 potential mother-infant burials are reported.

Consequently, we advise that pregnant ladies who died weren’t routinely buried with their unborn youngster and should not have been commemorated as one, symbiotic unity by Viking societies. The truth is, we additionally discovered newborns buried with grownup males and postmenopausal ladies, assemblages which can be household graves, however they could even be one thing else altogether.

Matt Hitchcock / Physique-Politics, CC BY-SA

We can not exclude that infants—underrepresented within the burial file extra usually—have been disposed of in death elsewhere. When they’re present in graves with different our bodies, it’s potential they have been included as a “grave good” (objects buried with a deceased particular person) for different individuals within the grave.

This can be a stark reminder that being pregnant and infancy might be susceptible states of transition. A ultimate piece of proof speaks so far like no different. For some, like Guđrun’s little boy, gestation and start represented a multi-staged course of in the direction of turning into a free social particular person.

For individuals decrease on the social rung, nonetheless, this will likely have seemed very totally different. One of many authorized texts we examined dryly informs us that when enslaved ladies have been put up on the market, being pregnant was considered a defect of their our bodies.

Being pregnant was deeply political and much from uniform in that means for Viking-age communities. It formed—and was formed by—concepts of social standing, kinship and personhood. Our research exhibits that being pregnant was not invisible or non-public, however essential to how Viking societies understood life, social identities and energy.

Marianne Hem Eriksen is an affiliate professor of archaeology on the University of Leicester. This text is republished from The Conversation below a Artistic Commons license. Learn the original article.

![]()

Trending Merchandise

Wireless Keyboard and Mouse Combo – RGB Back...

Wi-fi Keyboard and Mouse Combo – Full-Sized ...

Acer Nitro 31.5″ FHD 1920 x 1080 1500R Curve...

SAMSUNG 27″ Odyssey G32A FHD 1ms 165Hz Gamin...

NETGEAR Nighthawk WiFi 6 Router (RAX54S) AX5400 5....